May 11th, 2021

May 11th, 2021

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

This text is the first in a series titled ‘Decoding our Visual Practices’. Engaged with the visual translation of information and the power of this process as a democratising agent of hidden knowledge, Carola and Camille, two students on Visual Communication, came together in a collaborative discussion. Although communication among people has always been a contentious issue in society, it is even more complex when the message delivered is made up of technicalities that the recipients have not mastered , such is the case of Medicine, Law, Astronomy and Science. In this series of texts, we want to ask: how can encrypted concepts and topics be translated into a language that is accessible? Is design a tool for decoding or is it a language itself? Working as a facilitator between experts and the public, do designers and visual communicators become the authors of the messages they are translating?

Although the communication process itself is complex—even when senders and receivers manage the same languages—when the message delivered is articulated through aphorisms and specific terminologies, this process is even more cumbersome1.

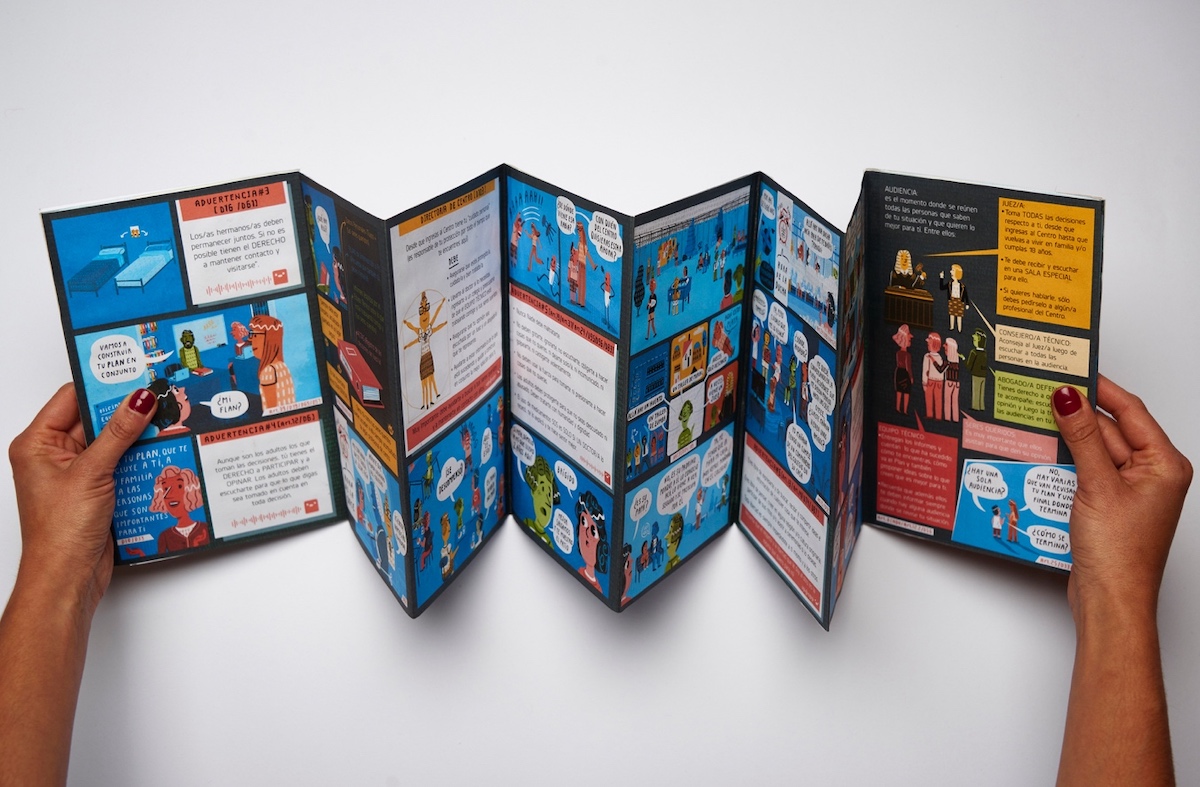

The Greeks called cryptography1 ‘the art of writing in a secret key or in an enigmatic way’. This word is integrated by two words Kryptós which means hidden and Graphé which represents the act of writing. It could be said that some disciplines continue working in a secret key that prohibits everyone from deciphering it. For example, thinking in the field of Law and in the drafting of statutes and regulations, the information is encrypted in its own covert system so that only lawyers, judges, attorneys and maybe some politicians can comprehend it. The legal system, such as articles and rights, are written in codes. How can the information be brought closer to people that need understand the content for protection, or at least because they regulate their communities? The Act of Parliament as the book that rules different societies must be accessible to all who want to inform themselves and be conscious of their rights.

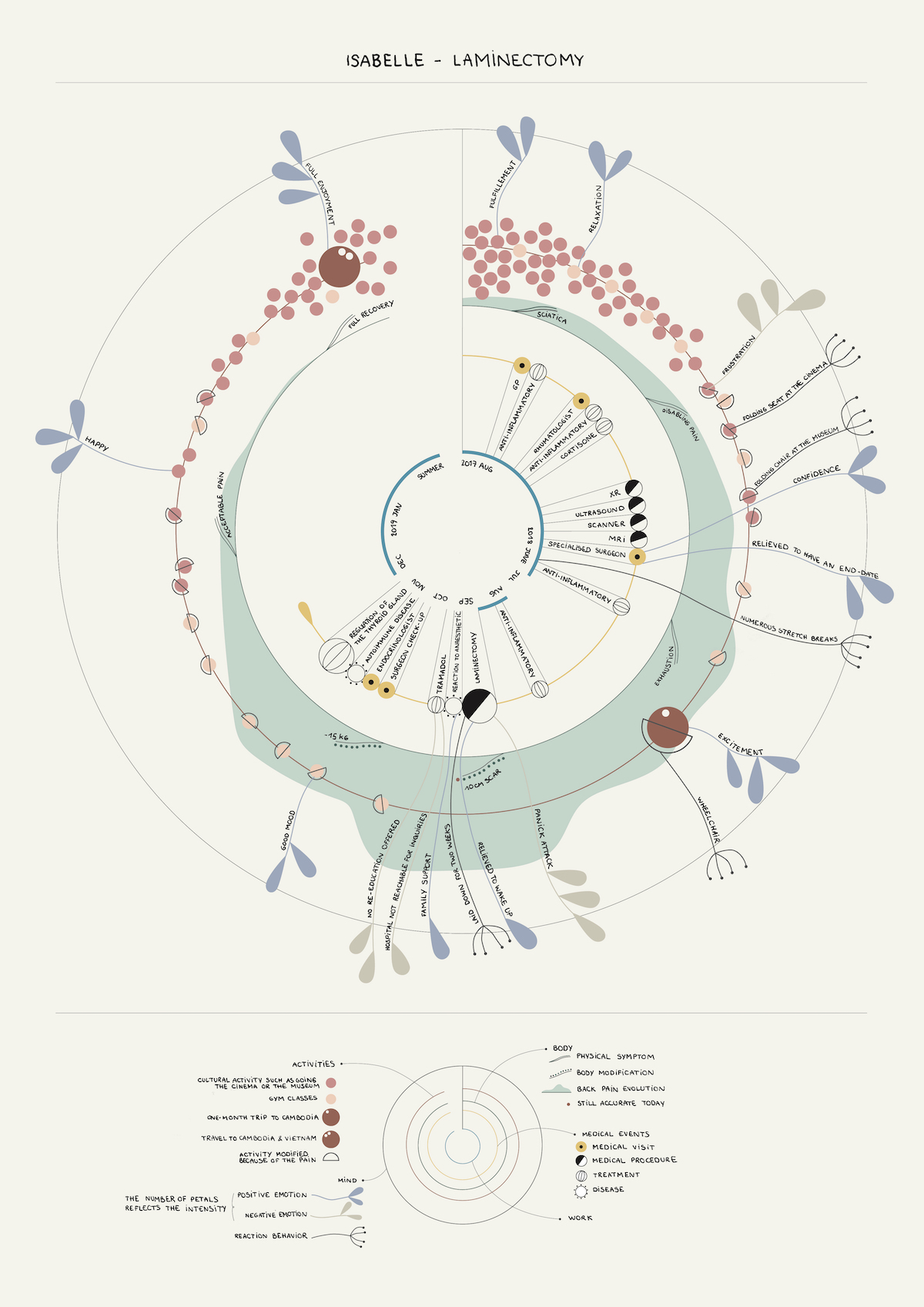

Similarly, Medicine operates with cypher concepts that patients can’t recognise and requires the translation of a specialist to decode their diagnosis. In this particular case it is even more complex because communicating an illness to a patient is also related directly to the emotional-spiritual side of each individual person. Medical reports generally contain words codified without a helpful or friendly way of reading them, not even a definition of keywords related to that particular diagnosis. People accumulate medical records that they are not able to interpret, leaving them waiting for the doctor in order to understand them. Therefore, the documents are not built for an open dialogue with the recipients, they are made only for the specialist. Most of the time, a patient’s data is gathered through drop down menu systems that respond to a rubric, but this method does not appreciate the uniqueness of each person. The options do not reflect all cases and therefore, it will appear that sometimes patient’s symptoms or previous antecedents never existed. How can personal feelings be part of the medical record? How can people communicate their pain to doctors and nurses? Can visual communicators create a scale of intensity common for patients with the same diagnosis? According to the Jamaican cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall, ‘the correspondence between coding and decoding is not natural but is constructed and requires an articulation’ 1. Could visual communicators operate as powerful orchestrators in these processes?

Visual communicators at the service of other disciplines, such as Medicine or Law, incorporate an ethical sphere within their practice, dignifying the role of communicative work. The process of decoding, articulating and selecting elements and finally, testing over and over again, can generate specific new languages for each particular case. Through their skills, visual communicators can create new symbol systems, use existing forms and even re-appropriate signs to build new notions that establish a common language, thus expanding the horizons of information transmission. Half a century ago, the French philosopher Michel Foucault published the book named “The Order of Discourse”. In this publication, he analyses the author as the first sender of a message and how the next messenger could disrupt the initial meaning causing a rarefaction of the original discourse1. What is interesting to notice in this idea, is that translating information can also make visual communicators authors of the new message, and in the same way now have responsibilities of the decoded content. The vision of a ‘democratic design’ of information also involves manipulating information and finally creating a new message. Helping to expand knowledge of people, according to Foucault’s thinking, visual communicators become authors of the message by operating as creators of a speech and finally, giving it their own interpretation and coherence. The role of visual communicators as those who decipher Laws, Medicine, and Science (among others), inevitably generates a reinterpretation of the information. Therefore, it is suggested that processes are carried out in an interdisciplinary context mediated by experts so that a translation can be achieved as unambiguously as possible.

Using the methodology ‘Thinking through making’, we are going to present and analyse some examples from our own practices as we go deeper in our work. In the next article we will extend this dialogue to explain some specific case studies that connect Visual Communication with, firstly the field of Law, followed by Medicine. This contribution is in no way a completed and finished body of research. Moreover, we define it as reflections that we want to open and share to develop and explore in our communicative practice. We are aware that working with other fields of knowledge and above all, when there are people involved, entails great responsibilities and duties to our profession and therefore we must be increasingly aware of the effect of our work.

Sincerely,

Camille Le Flem & Carola Ureta Marin

Acknowledgement

We would like to appreciate the work of Anya Landolt as the proof reader of this article.

Bibliography

Foucault, Michel, L`ordre du discours. [The Order of Discourses], translated by Robert Swyer. (Paris: Gallimard, 1970).

Hall, Stuart, ‘Encoding, Decoding’, Culture, Media, Language. Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79, edited by Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies University of Birmingham (London: Routledge, 1980).

Ureta, Carola, ‘·||[18.10.19/.cl/¡*!DNO