March 4th, 2019

March 4th, 2019

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

Equal Voices in the Room? Is a collaborative and ongoing project that explores the forms of discussion used in a pedagogical setting. Initiated by Cicilia Östholm and Alex Parry in 2017, the project primarily takes the form of workshops looking at how materials, structures and rules, actions and movement may all be part of discussion and how this may affect the participation of the group in the conversation.

The project sees group work as a microcosm of wider political systems, thus prompting questions about how democracy is enacted through speech and debate. Largely but not just contextualised within pedagogy the project demands a closer more caring look at structures and organisation within daily life and their potential to have political and social effect.

—

Cicilia Östholm in conversation with Laura Gordon, 4 Feb 2019

L: What was it that prompted you and Alex to start working together on Equal Voices?

C: Alex and I were on the Public Sphere pathway of the Contemporary Art Practice MA course together. During the first year we both observed that a lot of the discussions and group situations – whether in lectures, seminars or informally – tended to follow the same patterns. We recognised this pattern across the College but also outside the University. The pathway group came from all across the world, with so much to offer the conversation in terms of culture and knowledge, but unfortunately when gathered as a group it was only a few voices that would generally be heard.

We found that it wasn’t just Alex and me who were bothered by the lack of inclusion, but that this feeling was shared by the group more broadly. In the environment of the lecture or the group discussion it’s difficult to address the power dynamics directly while they’re playing out. If something is going on that’s borderline not okay, or you notice that only some people actually speak, it’s very hard to address when you’re meant to be talking about and focusing in another subject. We wanted to find a way of discussing the topic without it being divisive and give it our full attention – not just something that plays out in relation to other topics.

To have a proper look at this together, we used the format of a workshop that would be open to staff and students from across the RCA. The workshop became a combination of exercises borrowed from other practitioners, and ones we developed ourselves in order to look at power dynamics in the room. Some participants wanted to continue to discuss and develop the project, so we did a number of workshops collaborating with students across the College. Workshop participants suggested putting together an exhibition titled Equal Voices, which took place in the Dyson Gallery, and Alex and I later developed our workshop format for the degree show.

L: It would be interesting to find out some more from you about who turned up. I always assume that the people who are the worst offenders are the least aware of the power dynamics, and therefore unlikely to sign up to a session like this. Is that the case in your experience or not?

C: Based on the our experience, I’d say that’s most often the case. Probably the people that are the most concerned about power inequalities within a group are those who are either sensitised to it, or people who are directly marginalised by it. There has been exceptions though – we had one person who came to the workshop, who said that she is that person who would typically have a verbal presence in group conversation. But that she comes from a culture where you’re trained to do so, because you’re marked on it. And that her experience of being here, where people are not explicitly marked on verbal presence in the room or participation in conversation, had made her wonder what the experience felt like for others. So she approached this with an empathic and open mind, wanting to be more aware of this dynamic.

One member of staff raised a similar point, that maybe the people who would most benefit from doing the workshop aren’t necessarily in the room. And suggested that you should do it with the RCA management team and board. Again, the people who actually have the most influence would perhaps not think to participate.

L: Did you experience any pushback throughout the project?

C: Of course we’ve had participants at the workshops who have given critique and feedback, both in terms of sharing their experiences and what’s not worked for them within the workshop. We always welcome this – it’s the best when people share and critique.

Doing the project as part of the course has presented some challenges where crit situations and tutorials have been a bit difficult. We were working together on the project, while the course had an unspoken emphasis on individuation. So it became difficult when we were being assessed. I think this is a shared problem for all kinds of socially engaged practices – talking about the collaboration itself, which may be a separate thing from the actual practice and from the visual and audible outcomes and so on. There’s a lot of different ways of talking about art and art practice that can sometimes make it too complex to talk about in 15 minute time slots. In this way there has been some questioning from the institution, but we’ve had a lot of encouragement. And it feels like the minor pushback and the encouragement ensure that the project is relevant. Because it proves itself in the doing.

L: When you were talking about your project in a group scenario, did the group always seem hyper aware of their own behaviour in relation to your project?

C: Well, this is the funny thing – I don’t think so. I think it offered a space for the people that had a need to discuss things in another way, and for me personally running the project in part provided a safer space with people operating as allies. It’s subtle, but just knowing there’s somebody else in the room with a shared understanding gives you a sense of ’I’m not the only one noticing this’ or ’it’s not just me being obsessed.’

Our plan from the beginning was to run a workshop with our own group, that was the aim, to see what would happen. And we never got to this point. We were always unsure of how that would be perceived.

L: That’s really interesting that you never did it with your own group. Someone told me about this idea that the way you function in a group is connected to the role you play within your own family. So people are often drawn to groups that are similar in size or dynamic to their own family setups – your ‘original’ group. I wonder if the way you spoke about your ‘own class’ could be slightly analogous to your ‘own family’. To meddle in your own family roles or system is very difficult and exposing work, so of course it feels different versus doing it with acquaintances or strangers.

Could you talk us through your favourite exercise from the publication?

C: One that we always do is the mind map one, which is drawn from Jo Freeman’s text The Tyranny of Structurelessness. Our reading of this text is that striving for non-hierarchical group situations is a good aim, but it’s never going to be realised. You have to acknowledge what’s going with power hierarchies, even implicit ones, to be able to do anything about them.

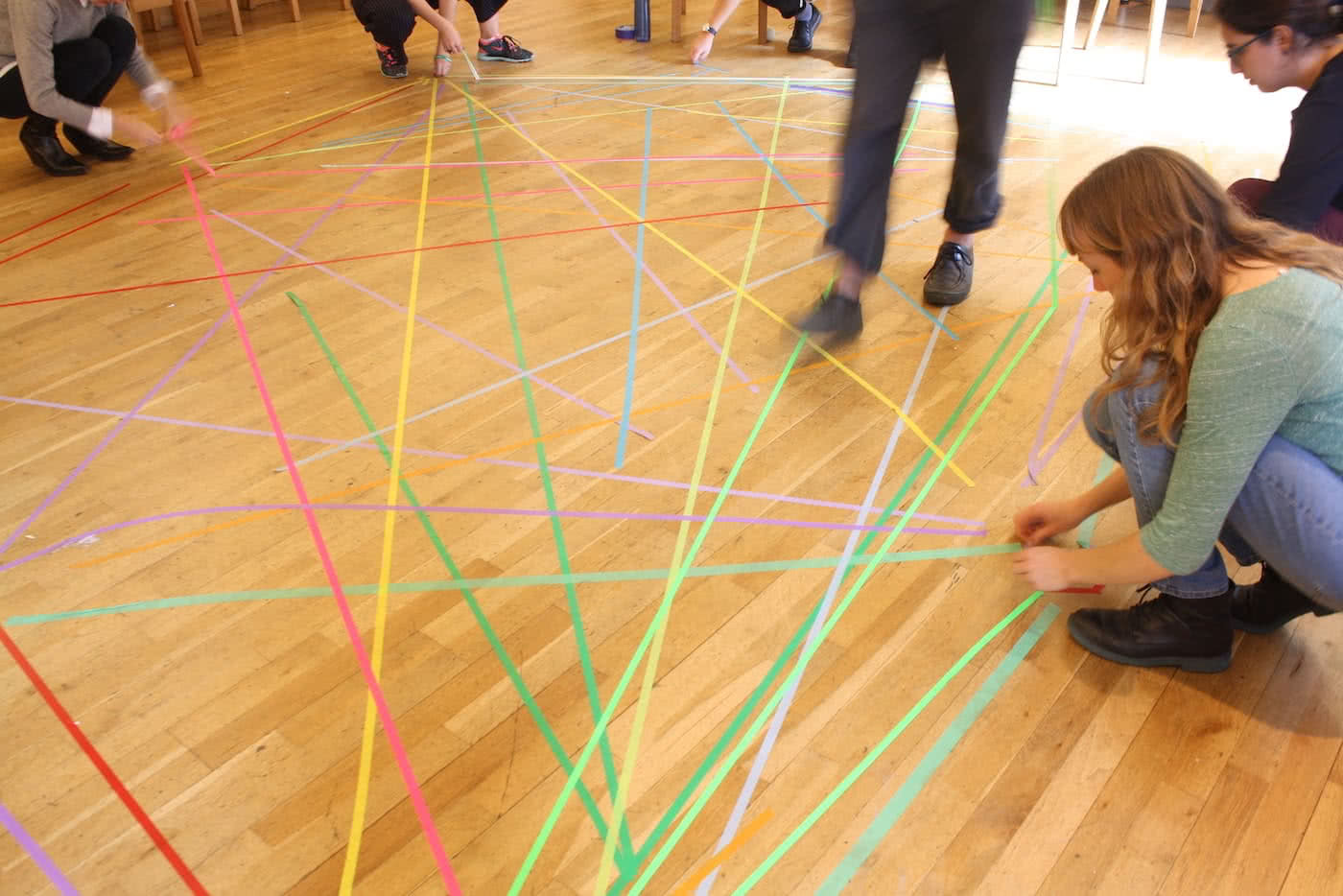

The mind map allows us to make the power structures of the group very explicit. In each workshop we introduce the exercise and then make a big mind map together, drawing lines between the people to map their experiences or perceptions of power dynamics. We’ve worked with the mind map in different ways, for example it became a piece of fabric for the degree show, where we did group embroidery sessions on to it while drinking lemonade and eating biscuits. Working with the material in this way attracted a different group of people, which made for another kind of discussion, where the material object in part mediates the discussion and intra-social experience.

L: In the session I was in, I really loved the group exercise you started with which was about sitting in silence together. It doesn’t come naturally to me and it’s something I’m trying to get better at in my teaching practice. That’s something I’ve seen tutors do a lot, myself included – feeling like holding a room means making sure that there is always sound. When of course silence is a natural part of conversation. So that silence exercise was really helpful for me as a reminder of what could happen if you didn’t fill in the gaps. Or what those gaps might allow other people to do.

C: In Equal Voices in the Room we think a lot about the role of the listener, not just the speaker. The speaker is the most researched and the most socially and politically revered. This means that the listener disappears. One of the things I’ve noticed being a non-native English speaker, and being in a room that’s a mixture of second and first language speakers, is that pauses of silence make a big difference in interrupting this fast-paced-discussion-at-all-times model. And ideally the person leading the group or in role of the moderator, doesn’t always to respond to silence with ‘okay now I have to find a new angle’.

I heard a podcast with Sophie Hagen, a Danish standup comedian, who mentioned that if you’re broadcasting live sound, and there’s more than 3 seconds of silence then they’re going to break for commercials. I haven’t been able to find out if that’s true but I think we’re also trained out of silence through our media outlets and politics, and it plays out in our social relations.

L: I’d like to come back to this statement in your manifesto [in the publication] ‘We believe the role of the listener can be used as an act of solidarity when others are speaking truth to power’. When I read that back this morning that felt so relevant, both to the RCA but also in a much broader sense. About the act of listening as a deeply political, powerful one. There’s this incredible image that I’ve become obsessed with that was taken during the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, and there’s a woman on the steps of the Supreme Court telling her story to a crowd. There are four older women behind her, with their eyes closed, and they each have a hand on her shoulder. When I read that line I thought of this image. She was speaking and they were supporting her by being present, by holding her and by hearing her.

C: It looks like they’re healing her.

This listening is relevant in online groups too. I was part of a group of performing arts, dance and choreography women, non-binary and trans people who engaged in the #MeToo movement. There were thousands of people in the same social media group, listening to each other, and even if you didn’t comment you could ‘like’ and just be there and witness what others shared. In Sweden the movement has had real effects, contributing to changes in legislation on sexual consent, which is incredible. It’s still a really strong movement, and it has been made possible through acts of solidarity, and lots and lots of people just listening, being present and not responding in a way that undermines that person who is speaking.

L: So what’s next for the project?

C: We’re looking at how to develop the format of the workshops, applying for residencies and funding and exploring how we could work within other learning environments, for example school councils. We’re also interested in how we can involve others who are interested in doing their work as part of this framework. So we’re in the process of pursuing different possibilities and opportunities, but we’re not set yet on where it goes, which I think is a good thing. Because our aim is to continue to work with other people and not get sucked into the idea of what we think it is now, or of authorship.