June 11th, 2021

June 11th, 2021

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

Inbetween: Countries & Cultures, is a space for candid discussions around transient identities as individuals move to a new country of residence. In this space, the individuals share some anecdotes from their life and experiences as we make our way through a new space, culture and society.

Rathna Ramanathan is a typographer, researcher and educator. Originally from Chennai, India, she is now based in London. She is currently Dean of Academic Strategy and Reader in Intercultural Communication at Central Saint Martins and is our former Dean for School of Communication and Head of Programme for Visual Communication. Her research and practice are predominantly focused on the Global South, specifically South Asia. Intercultural practice is central to her approach in learning, teaching and research. Through this conversation she tells us about her familiarity of living in ‘between’ as an individual across languages, countries, and experiences. She provides valuable insight into her position as a creative practitioner situated between two cultural contexts with a focus on intercultural communication.

The concept of being between is familiar to me. In 2016, I did a pecha-kucha presentation to Visual Communication students and staff on this theme, as the then Head of Visual Communication. What I spoke about mentioned that:

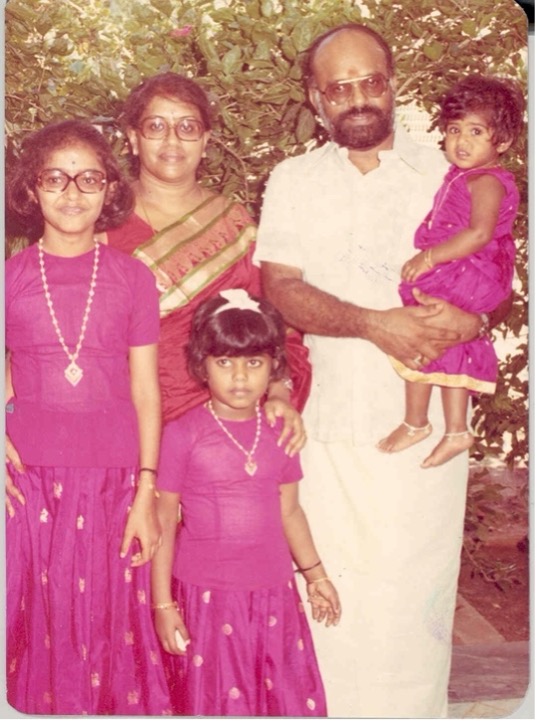

I am one of three children. I am born between my two sisters—about 4 years apart from each other. I found being between useful because I could get on with things without drawing attention. It was that between that helped me find my creative spirit, my imagination, myself. In family pictures, you can recognise me as the one that’s always caught between a smile and a glare.

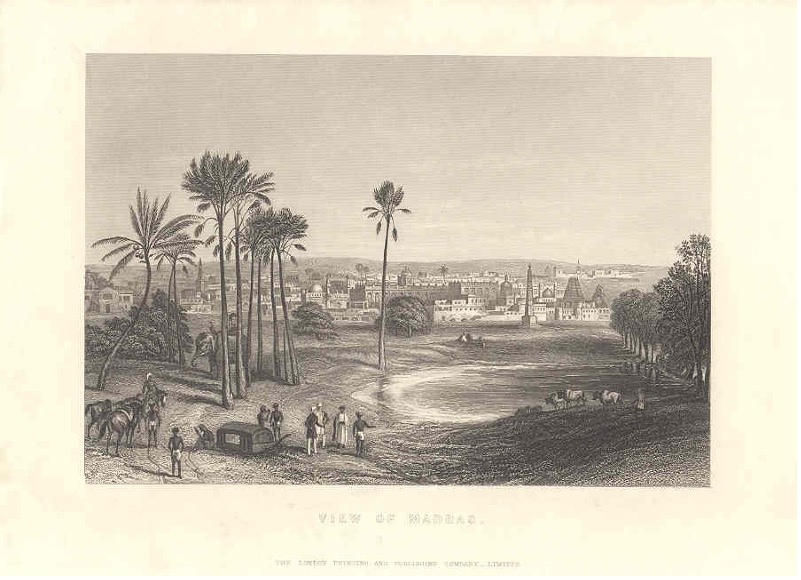

I was born in a place that has two identities. When I was growing up, it was called Madras. But the correct way to refer to it today—the post-colonial, non-British name—is Chennai. Depending on how homesick I am, I toss between the two names. You could say, I am between a Madrasi and a Chennaite.

My brain lives between two languages. I grew up speaking Tamil at home. But I come from a middle-class family, which means I went to an English-speaking school. Sometimes the sentences I write in English are not quite-English but between Tamil and English.

As a child I was always caught between tastes. My favourite biscuit in India was called 50-50. It is half sweet, half salty. That’s still how I order my lime sodas in a restaurant. It was only when I came to the UK that I realised I had to choose one taste. British biscuits were such a let-down for this reason.

In India, with a billion people fighting for resource, you are constantly confronted by lack, by adversity, by the constant guilt of having more than most people you encounter. The only thing between you and the person with less, was the car window wound up, with the warning to give food but not money. This still doesn’t make any sense to me.

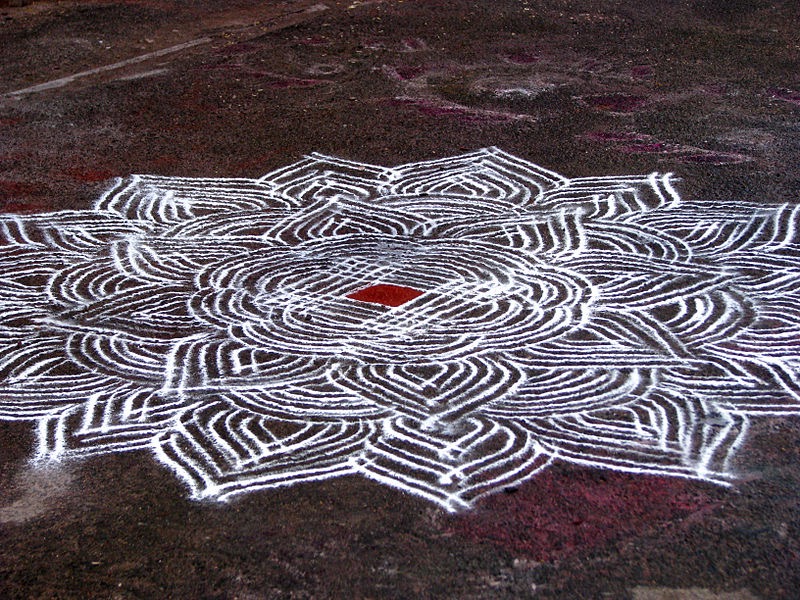

When I was growing up, I drew rice flour kolams with my grandmother joining up the dots between the lines. The kolam is a welcome – a daily invitation to not just humans, but to the ecosystem of ants, squirrels, crows. By the end of the day, this intricate design gets eaten up, walked over, and disappears between the pavement cracks. I live in London now but I draw these kolams every January to celebrate the Tamil harvest festival—Pongal.

I grew up and live between cultures. My mum is of Sri Lankan descent, holds a British passport and went to a Catholic school. My dad is Tamil and grew up in rural India. For both of them, and subsequently for my family, rituals became the acts that bound them to community, culture, identity, and memory. I’ve created this same binding with my American husband. Every year, my daughter celebrates Diwali and Thanksgiving. Her open embracing of these traditions between an American dad and Indian mother makes me reflect for myself.

My status in the United Kingdom for the longest time—till 2020— was one of an Indefinite Leave to Remain. Between sometimes means you don’t belong. Adorno notes that the only home truly available now, is in writing. In practice. It is part of morality, he said, not to be at home in one’s home. To follow Adorno is to stand away from home in order to truly look at it. To be between.

This thought of not belonging came to my mind when I first came to the Royal College of Art in 2015. I was an Indian citizen in a British imperial institution. There was always that tension, always that in-betweeness. For the entire time I was at the College, I was one of two women of colour in the School of Communication.

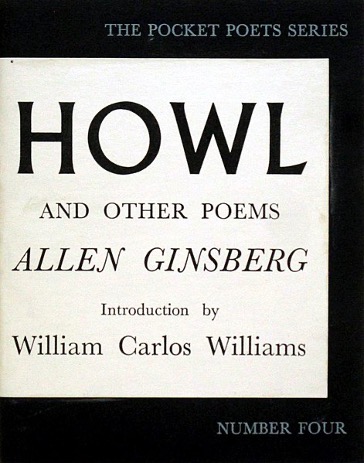

In my PhD, I came across Allen Ginsberg. In 1965, Ginsberg performed the Howl at the Royal Albert Hall. Howl was viewed as an obscene text; the performance an obscene act in an architecturally classical hall. I was inspired by Ginsberg who turned ‘not belonging’ into an act of humanity. For me, he performed this sense of the in-between beautifully.

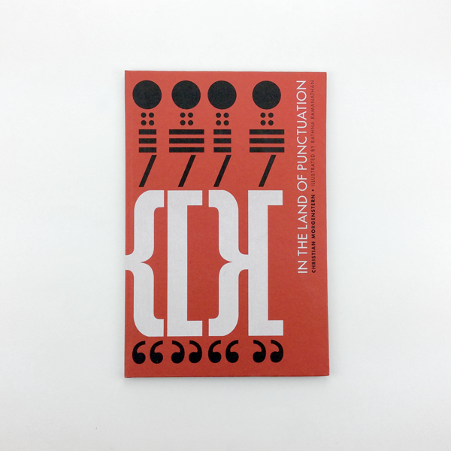

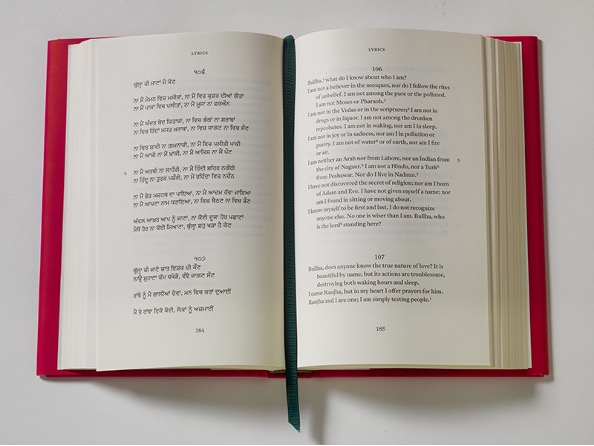

In 2010, my Indian publisher Tara Books gave me a text by the German author Christian Morgernstern to typographically illustrate. Written in 1927, the text on war, politics and suppression was neither for adults nor children but somewhere in between. I was neither the writer nor the translator, but I became one of the authors. Most of my practice sits between word and image because I grew up in a country where there isn’t a formal distinction between the two.

My studio projects sit between research and practice, between print and digital, between two languages, between cultures. I am based in the UK, but all of my work is related to India. I’d like to think my practice sits somewhere between the two countries, like a bridge.

Edward Said once said, exile is not a privilege but an alternative to the mass institutions that dominate modern life. Provided that the exile refuses to sit on the sidelines nursing a wound, there are things to be learnt: he or she must cultivate scrupulous subjectivity.

In Tamil, we have a saying – ‘Ithuvuman, Athuvum’ which means ‘this and that’ not ‘this or that’. Duality acknowledges that paradoxes can and must exist in the same space together.

So, between can be a useful place to quietly get on with things… where borders are crossed, where barriers of thought and experience are broken, where identity can be reformed, where both conflict and purpose can co-exist. Between can become an and. Between is a place and a practice where so many of us in-betweeners can find a way of belonging.