December 18th, 2020

December 18th, 2020

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

[FUGITIVE VOICES ACT IV, SCENE 1: Zoom Theatre]

*Together by Ruff Sqwad Riley plays in the background*

[Hook: Wiley]

(When we gonna) be together?

Never, we don’t wanna be with each other

I’m off to find a new lover

Cause this ain’t working, we ain’t working

(When we gonna) be together?

It seems there has never been a more fitting scene for these lyrics. In quarantined London, the absence of (mass) physical interaction rings through the voided streets and bangs with disconnection in our virtual classrooms. It’s daunting to think that we today will be talking about togetherness and community engagement with Abbas Zahedi—the fourth guest on Fugitive Voices.

[ENTER ABBAS ZAHEDI]

Zahedi makes a theatrical entrance against a backdrop of what looks to be a well lit basement. Surrounded by an eclectic array of props transforming the lecture into a scene d’exposition (introductory scene of a story), he softly speaks into the podcasting mic: “There won’t be much of me talking. I want this space to become an opportunity for conversation”. Bringing another dimension to the liminal realm of Zoom, he was a hakawati (a storyteller), telling the story of his practice, life and journey into the art world.

[ENTER ART WORLD]

Having infiltrated the art world through spoken word (lyric writing), Zahedi fits word-as-medium like a glove and chooses his words carefully. Linguist and polyglot, he sees the sonorities and flow as carriers of message to be handled with caution; for him a slight turn of phrase can be the difference between building or burning bridges between people. Often using psalms, poetry and lamentation as transmitters for his work, he honours the Middle Eastern oral traditions as a powerful source of knowledge and community building, too often disregarded in the Western tradition of learning from written documents rather than from others’ voices. His performative lectures, MANNA from below (2019) catalyse his research via his voice. Speaking about identity, cultural absorption and the motivations driving his practice, he calls out the audience on notions of legitimacy and lack of real interest towards the ‘other’: “Because my past is heavy, it is too much of a burden, people can’t relate to its particularities, the punctum of its weight.”

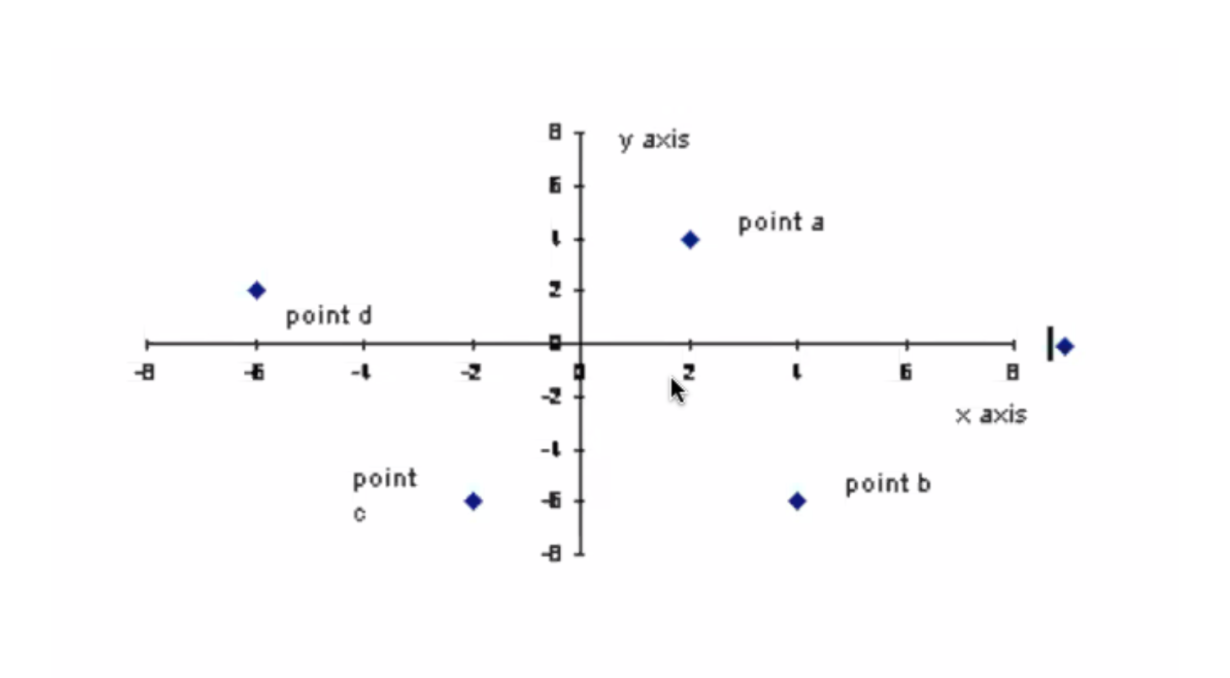

With Iranian heritage, he considers himself part of a neo-diaspora. The addition of “neo” suggests something beyond being a second or third generation migrant or speaking about the circumstances of moving from the margins into the metropolis. For Abbas, neo-diaspora echoes out of the ever-growing, entangled landscape of multiple identities and places of belonging. It becomes a complex process of survival. This dilemma could be pictured as a suffering reality, however Zahedi sees it as an opportunity to map out a fugitive existence (x axis as “fugitivity factor”) against the Y axis of the Fine Art canon.

By inviting us to consider ourselves within this topology, Abbas reminds us that none of these positions are fixed for fugitive voices. Whilst a fugitive seeks to escape, not to be located, and to break free from constraints through drift, they might require a map to orientate themselves (SEE FIG. 1). This statement particularly resonated with us. Being second generation Middle-Eastern and first generation post-Soviet migrants, we are often confronted by the insider/outsider position, and endless calls to justify and explain our polyethnic identities, with “where are you from?” being the ultimate trick-question in first encounters with strangers. Does pinpointing or triangulating our cultural contexts cultivate connection? On the contrary, Zahedi creates space for gentle confrontation through obtuse incomprehension. His practice reactivates and transforms personal memories into new collective experiences through the act of sharing them with a Western audience, for whom their context might appear alien, even reading them as gibberish. This awkward system of mistranslated and incomprehensible encounters destabilises the axes of fugitivity through the indeterminacy of poetic hermeneutics, and subverts the idea of “engagement”. Unexempt from this effect, we too were dumbstruck by Abbas’s mysterious lecture title, “Together in networked solitudes of control a.k.a. How to swim good in an empty sea of images” and a curious term, “relational aesthetics”.

[ENTER AUDIENCE a.k.a. WTF is “relational aesthetics”?]

Our secret confusion at these words was comforted by other shared looks of puzzlement in the room that we read as: WTF is “relational aesthetics”? After a quick Google, we learnt that the term was coined by the art critic, curator and historian Nicolas Bourriaud. His eponymous book Postproduction (1998) heralds community engagement artists like Rirkrit Tiravanija, Thomas Hirschorn and Tino Seghal, and defines RA as:

A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space. (pg. 113)

This term refers to artistic practices that take lived life as medium, and engage the audience in the making of the work; the way we understand it, this is akin to conducting a social experiment inside the art world. In essence, this is art-practice-as-scripting and practice-as-enacting social situations, staged within gallery or museum walls with props of daily-life-objects, removed from their original context. As opposed to the object being the centre of attention (worship), what matters is the happening (ritual) between people during this social event.

Zahedi presents us with the friction points of RA, considering the parameters of set up, audience and tone of voice. To illustrate his point he reflects on his participation in the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017. His participation in this art-colossus gathering was a socially-minded experiment in how his work is perceived across class. Seeing himself as an outsider in insular ambience, he saw the private view—a boozy celebration—as an opportunity to reflect on cultural consumption and appropriation through his opening performance #FakeBooze. Hijacking the drinks bar and unsuspectingly leaving the bottles of his handmade drink, Shandy Saffron, around the pavilion, the drink was a ‘relational’ trojan horse, walking into power structures. Photographs documenting the event show ‘guests’ cheersing, and expressively gesticulating with large arm gestures and broad smiles, as if faking tipsiness. Reflecting back on his own performance, we hear a derisive note in Abbas’s voice: “These were all interesting questions and points made during this ONE event, but what’s next?”

[EXIT AUDIENCE]

From washing dead bodies of his family members, to watching acquaintances leave for radicalised religious quests, Abbas Zahedi’s most recent work draws directly from lived experiences. He doesn’t shy away from his encounters with death, grief, faith or violent nuances of border relations, nor from their corporeal residues. In his latest exhibition How To Make A How From A Why? (2020) at the South London Gallery, in the face of total digital sanitisation of art spaces overnight, Zahedi persisted in developing a physical and sensory-oriented intervention—a daring task in a situation of touchless semi-lockdown drowsiness. Set in what used to be a Victorian fire-station, Abbas leaves a dispenser of rose water, tempting the visitors to pump it through the fire-sprinkler piping (he taught himself plumbing to do this). The pipes fit seamlessly along the gallery ceiling, making you wonder if it was there to start with, and connecting to a range of unfamiliar-looking vessels like bowls and jugs—a connection to his family of Iranian ceremonial drink makers. The gallery becomes a remembrance site of sleeping archives, awakened by the visitors touch.

Reflecting further on the idea of threshold and right to entry, Zahedi intercepts the gallery’s architecture. Rather than putting up fences and barbed wire, he transforms doors and shutters into transducers that play a collated soundscape native to Iran. This sonic exploration, In This Space We Leave, accompanies the visitors throughout the exhibition, whilst adapted exit signs gently drop hints throughout the space, politely directing the public to leave the gallery. The bodily investment from the audience to squeeze the pump is an invitation to participate, but perhaps also a clue to a daunting realisation: to what extent is our presence awakening as opposed to disturbing this site? What good is our engaging in this site of grief?

[ENTER DIPLOMACY a.k.a Do we negotiate with White Saviours?]

In recent years, the ‘white saviour performance ’ is widespread in the Western art world, with recovering inclusion and involving socialisation at the centre of the curatorial agenda. Furthermore, as the audience, has our yearning for sincerity and interaction so embedded within Western society characterised our defiance towards the authoritarian artistic elite? Does this then perpetuate the curator’s ongoing quest to platform fugitive voices? If so, do these artists become spokespeople, ventriloquising the voices of art institutions’ diversity and community engagement concerns?

Zahedi is highly aware of this ‘socialisation’ trend, but rather than rejecting the art world, he treats this encounter as he would any other… The artist negotiates his terms and proposes convivial antagonism as a way to re-navigate the audience. ‘You don’t have to smear shit on the walls to challenge the audience’, he states. During the Q&A he talks at length about acting diplomatically when approaching gallery commissions. ‘Working with curators is about being curious’, he highlights, ‘from both sides’. Conversation is what allows fugitivity to penetrate the art world: from religious prayers of “the other” echoing through Victorian corridors, to co-opting champagne socialism and spiking hipsters with cheerful sobriety, to fragrant ritual-washing of untouched, sleek institutional surfaces, to whispering signage escorting the prying eyes of visitors out of the gallery. Abbas Zahedi’s oblique and wayward disengaging of the participants in his neo-diasporic work is what leaves a lasting impression of sincerity.

[EXIT ART WORLD?]

As art institutions become ‘hosts’ for social interaction on a mission of inclusion, the future of ‘Relational Aesthetics’ and the authenticity of ‘fugitive’ practitioners is certainly in question—what’s next for the future generation of artists and communicators who seek to engage? Zahedi cautions against the pitfalls of Neo-Orientalism that would over-romanticise his voice and remove it from its core concerns: the set up, the audience and the tone of voice. As a final recommendation, he shared with us an essay from an artist Coco Fusco, “We Need New Institutions, Not New Art”. This writing poses the statement that equity and intercommunication won’t be solved by programming new events: “If progress is desired, we need to look back and make sure not to repeat history, not try to invent something new”. With art institutions seeking to re-appropriate, re-engage and de-colonise, does it make sense for the neo-diaspora to lead a reverse-crusade, mapping out spaces against the Y axis of the canon? Or would it make more sense for the fugitive to flee, to drift, to disengage—find their escape off the charted territories of the art world?

[END LECTURE]