June 25th, 2018

June 25th, 2018

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

How, in their everyday life, do women navigate public spaces, like walking home or travelling from one place to another?

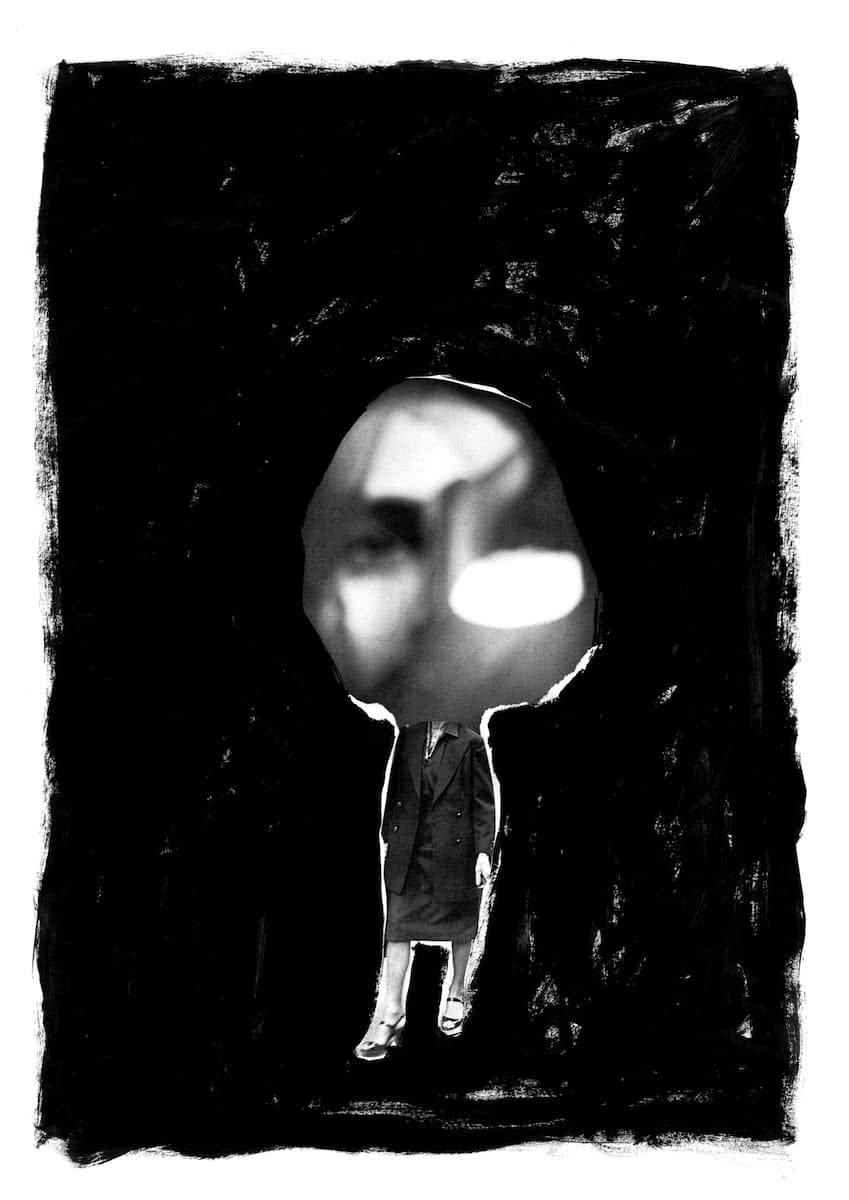

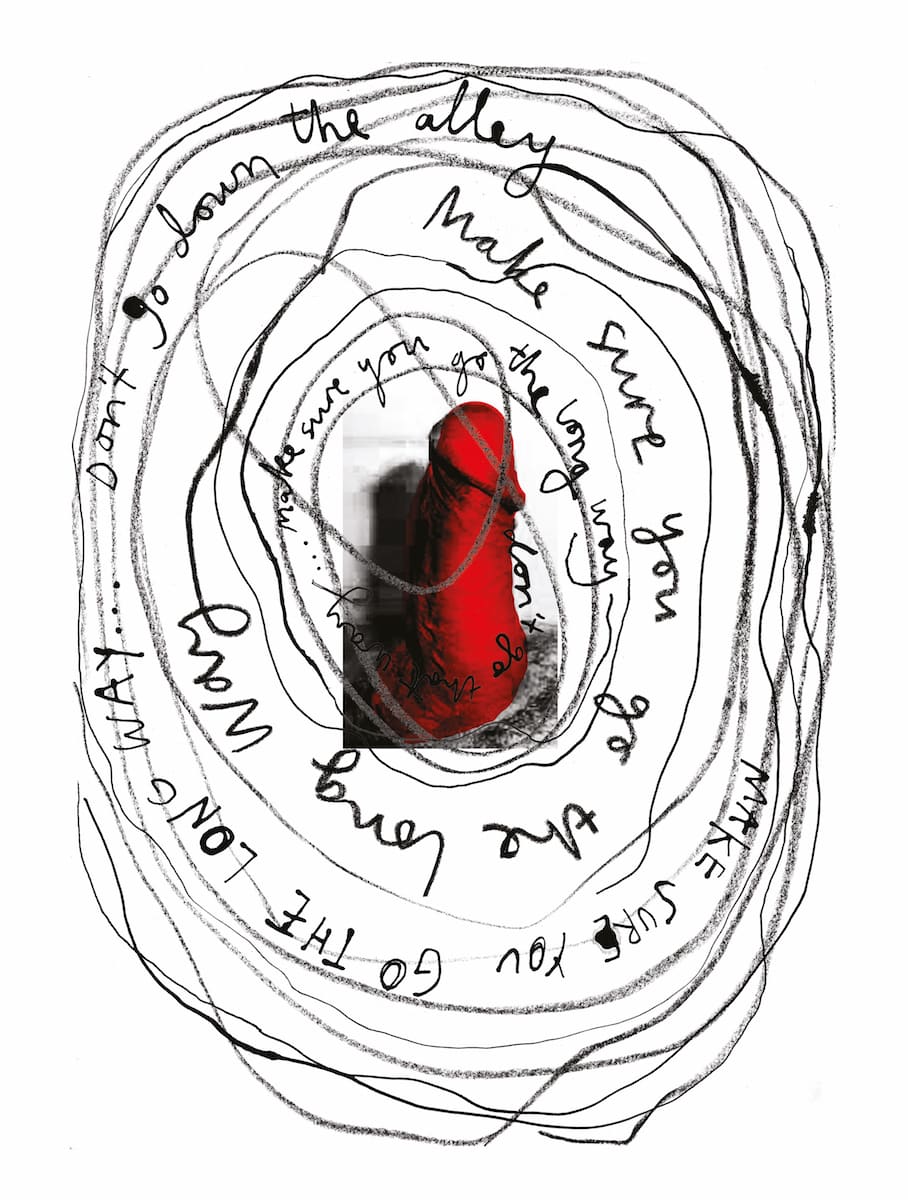

One night, after a night-out with friends, I got on the bus and took the long way home alone. I didn’t even think about it, it was a no-brainer, that would be the route I took home that night. I was aware I was doing it, I had to do it, because if I went the other way it would mean that I would be left scared and vulnerable, as I walked the poorly lit streets back from the tube station. Whereas, this way, I would (most likely) be safely dropped around the corner from my house, on a well-lit street. But why did I take this inconvenient route back? My unconscious-self feared attack; she feared rape; she feared murder; she feared all of the things you hear about and dread ever happening to you. She was ready with her plan to attempt to keep me safe from unthinkable acts.

Whilst waiting for that bus, I was approached by two men. They “jokingly” told me that I should join them at a nightclub if the bus was to be much longer. Despite being intimidated, I confidently laughed it off, as if to shout “hahaha, I’m not scared”. There she was again, my unconscious self, trying to diffuse the situation, trying to avoid any further possible aggression or confrontation that may have come with a refusal. It was this experience that left me questioning, even more so than before, all of the experiences and encounters that are shaped by a misogynistic culture, that women are confronted with when navigating public spaces. These everyday experiences may not necessarily be “newsworthy”, but the phantoms that women encounter – the anxieties and feelings, and the intrinsic fear of gendered aggression – all stem from deep-rooted, destructive, patriarchal systems and values.

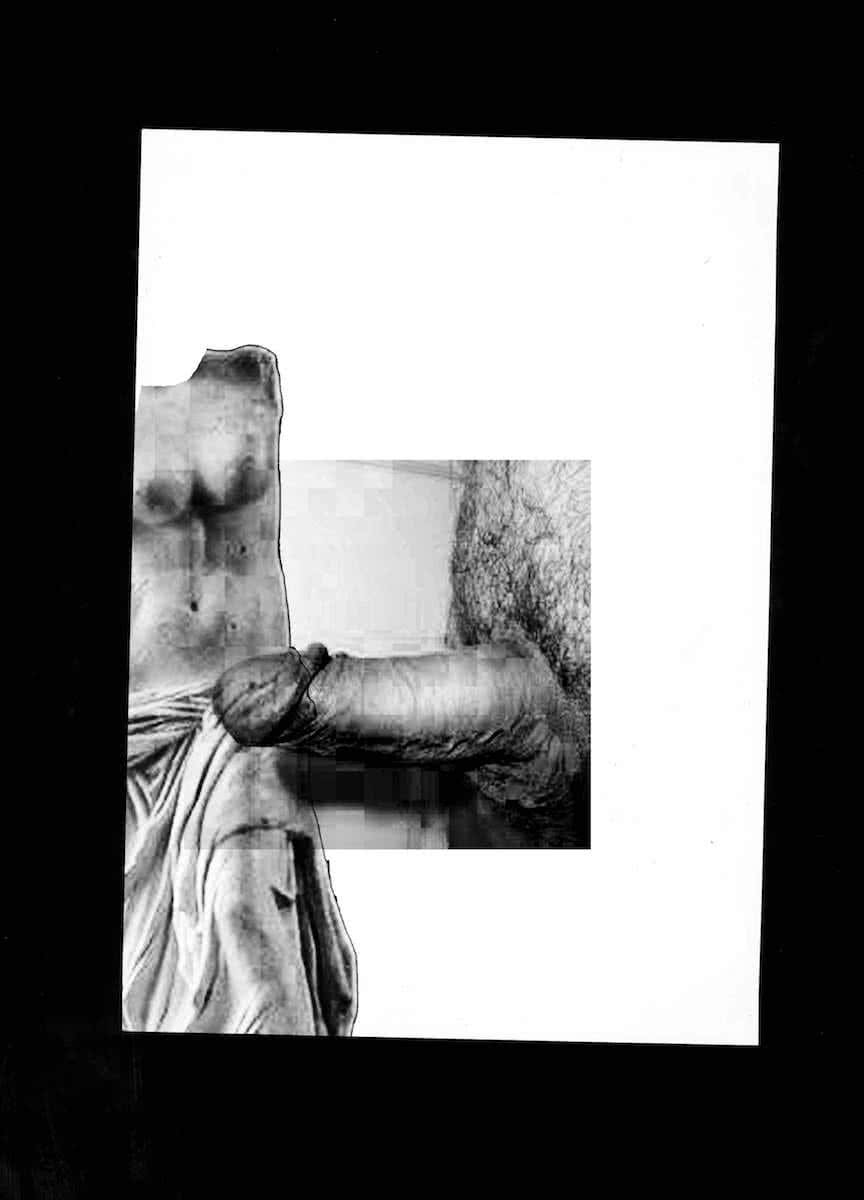

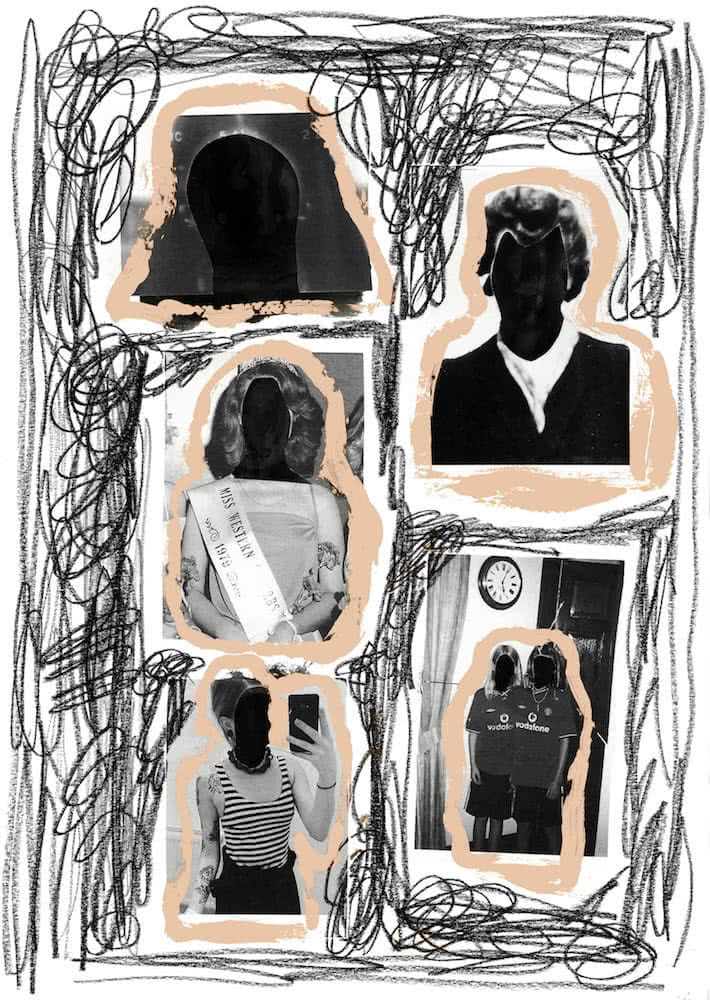

We are born into our culture. We are born into the gendered codes and conventions that go on to define our position in the world (Butler, 1990). We are born into an unreal reality, made real by the constant representations of a patriarchal, gendered socialization, which we then internalize (Chimamanda, 2014:30).  ‘One is not born, rather one becomes a woman’ (De Beauvoir, 1949:301). As a woman, I am a victim of my culture. I have been shaped by my society and, despite being in a supposedly privileged and empowered position in the modern Western world, I am still a victim of my culture, navigating the everyday oppressions that shape my existence.

‘One is not born, rather one becomes a woman’ (De Beauvoir, 1949:301). As a woman, I am a victim of my culture. I have been shaped by my society and, despite being in a supposedly privileged and empowered position in the modern Western world, I am still a victim of my culture, navigating the everyday oppressions that shape my existence.

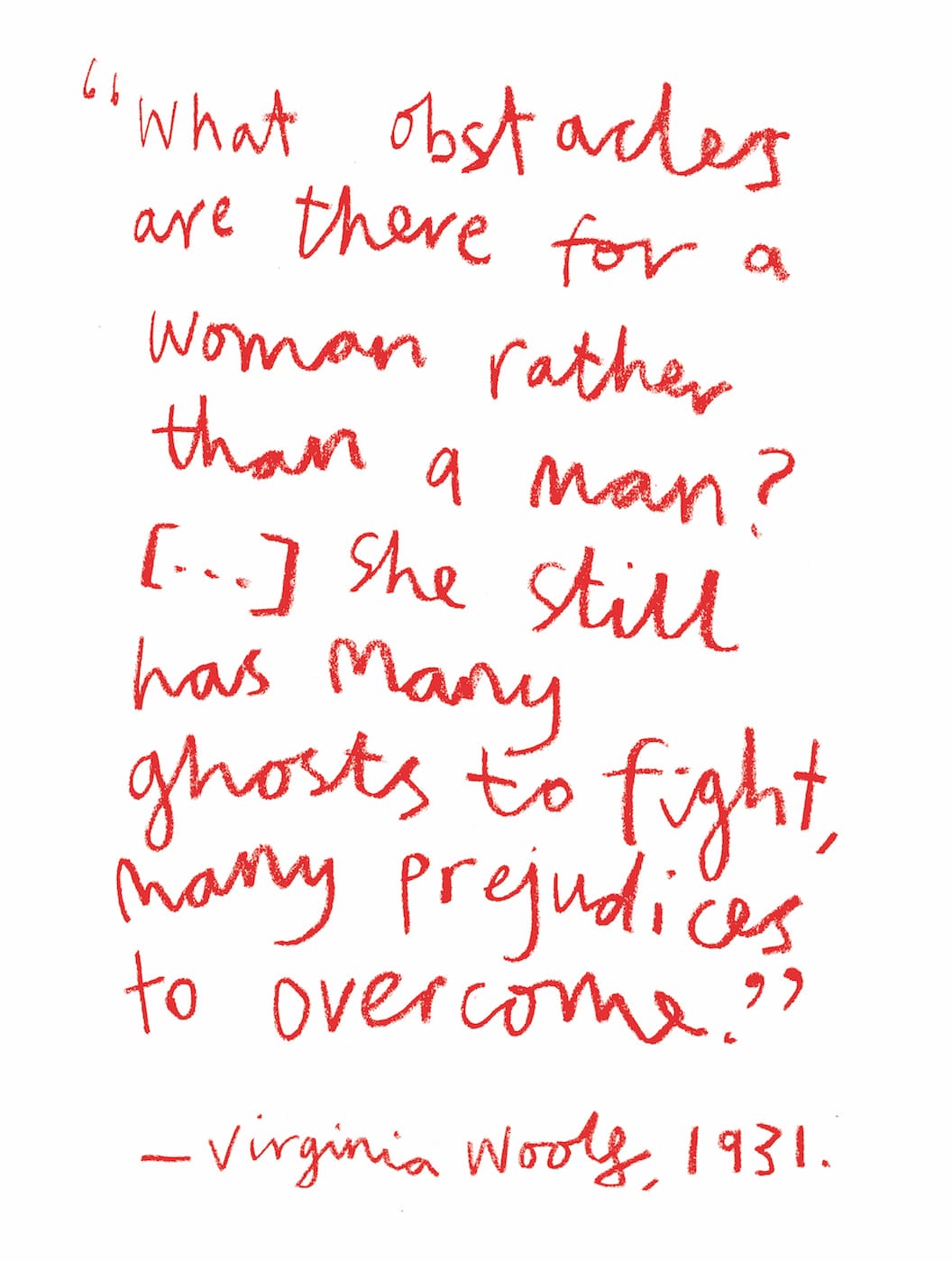

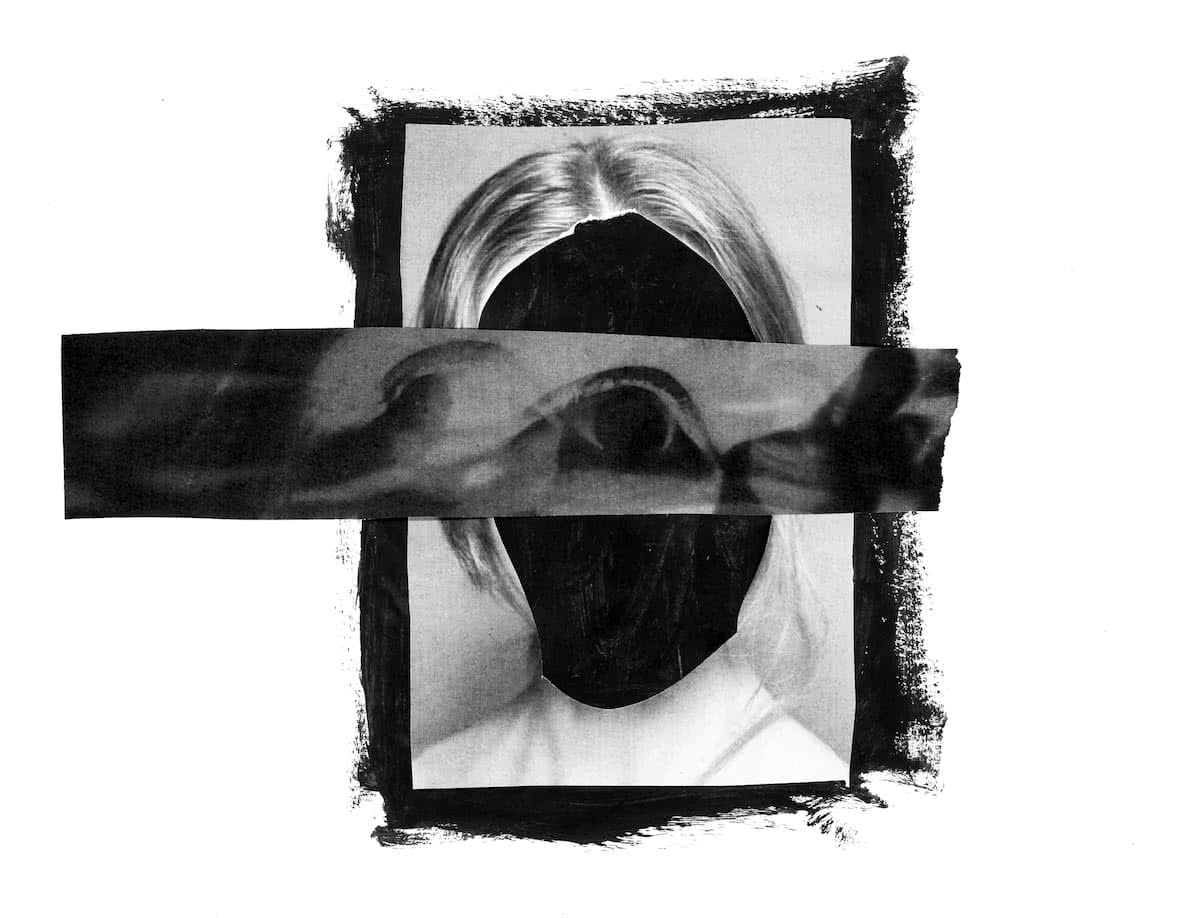

‘Even when the path is nominally open – when there is nothing to prevent a woman from being a doctor, a lawyer, a civil servant – there are many phantoms and obstacles, as I believe, looming in her way. To discuss and define them is I think of great value and importance; for thus only can the labour be shared, the difficulties be solved.’ (Woolf, 1931:8)

For decades, women have been attempting to reclaim and rewrite these frameworks. Although much has been achieved since the days of women being bound to the home, answering only to their husbands, there are still many forms of sexist, patriarchal aggression that attempt to keep women in an oppressed position. Many of these play out in everyday scenarios, becoming an almost “normal” experience, one so embedded that it feels almost intrinsic. Generations of women have encountered these hostilities, that sit somewhere along the misogynistic spectrum – from micro-aggressions, like being cat-called in the street, to extreme violence, such as rape and domestic abuse.

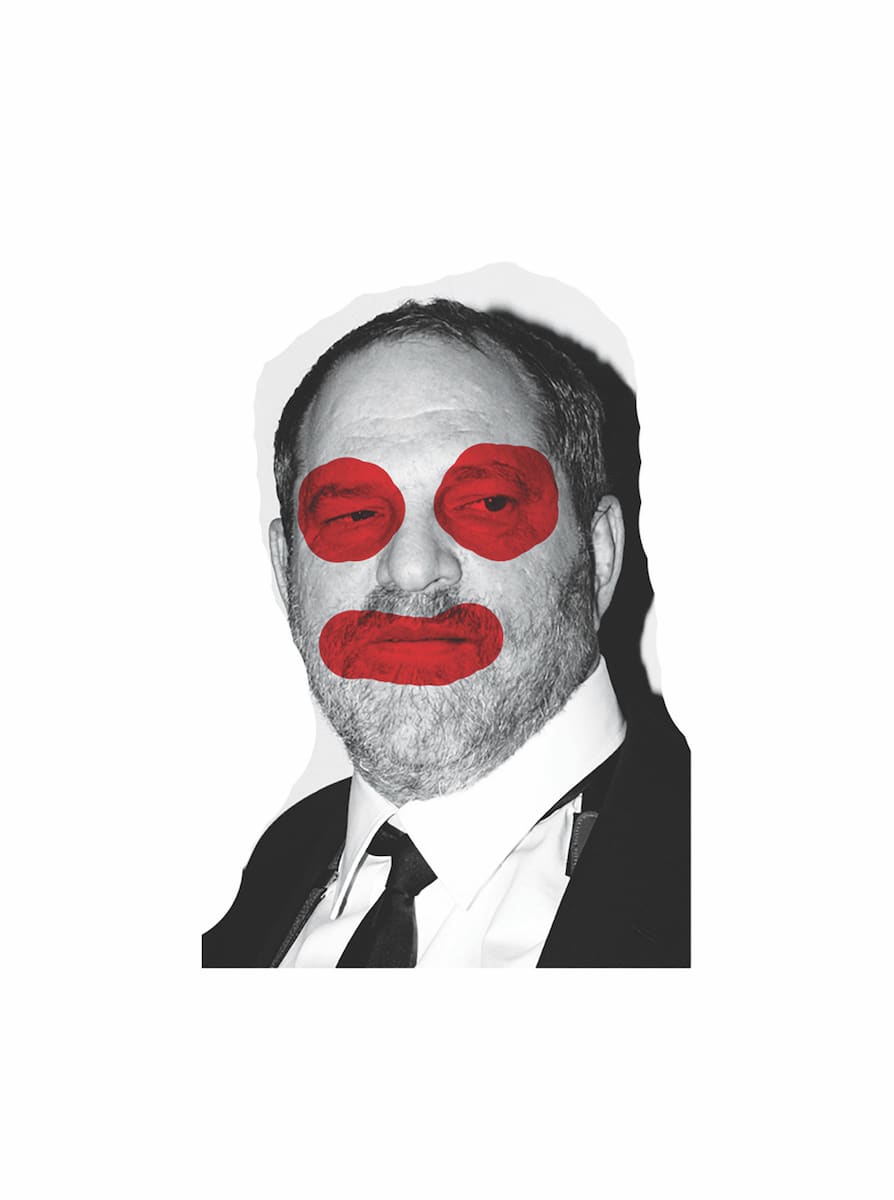

We experience these aggressions in many forms, from first hand encounters, to stories of rape and murder saturating our newsfeeds, all fuelling a fear for the “consequences” of being a woman. The everyday ideals, pressures, structures and positions, that are embedded in our culture, prevent us from progressing in our fight for gender equality. These are the phantoms of femininity and they attempt to govern us. The phantoms fuel anxiety and fear, and attempt to keep us in a vulnerable, secondary place. ‘It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality’ (Woolf, 1931:5). Even just walking down the street I am affected by my culture. It’s a space I have to navigate. It’s a space where I am confronted with many of these aggressions and obstacles, as I go about my daily business. But, what are these phantoms standing in my way? What haunts me as I navigate from A to B? From such a young age, I can remember hearing horror stories on the news of young girls being kidnapped, and I can’t even begin to imagine what else happened to them. Those fears didn’t just go away, they evolved over time.  Darker stories started to bombard me – stories of Weinsteins, attackers, rapists and harassers. Those stories shaped the way I navigate my world. Stories of girls being raped by taxi drivers as they make their way home; of attacks in the street; of lone women being sexually assaulted and murdered as they walk home alone through the park. These were stories of aggression, of gendered violence. These stories plaster the news, and more often than not, involve female victims. We are fed the fact that women are often the victims of violence carried out by men.

Darker stories started to bombard me – stories of Weinsteins, attackers, rapists and harassers. Those stories shaped the way I navigate my world. Stories of girls being raped by taxi drivers as they make their way home; of attacks in the street; of lone women being sexually assaulted and murdered as they walk home alone through the park. These were stories of aggression, of gendered violence. These stories plaster the news, and more often than not, involve female victims. We are fed the fact that women are often the victims of violence carried out by men.

“I can always remember having this fear drilled into me. I remember stories of children being kidnapped on the news. I can always remember being terrified of being kidnapped and god knows what else happened to them. I remember hearing it, and always being scared. There were all these myths instilled in us…”

“Don’t go near white vans.”

“Be safe.”

“Be home by this time.”

Those fears are still there…

“I was walking home from a club and I got off the tube a stop early so I could get some food. I was walking home alone and I rang my mum, it was around 1.30 in the morning. She was like “DON’T GO DOWN THE ALLEY”, well not an alley but a small poorly lit road near my house.”

“Don’t go that way.”

“Make sure you go the long way.”

Just in case…

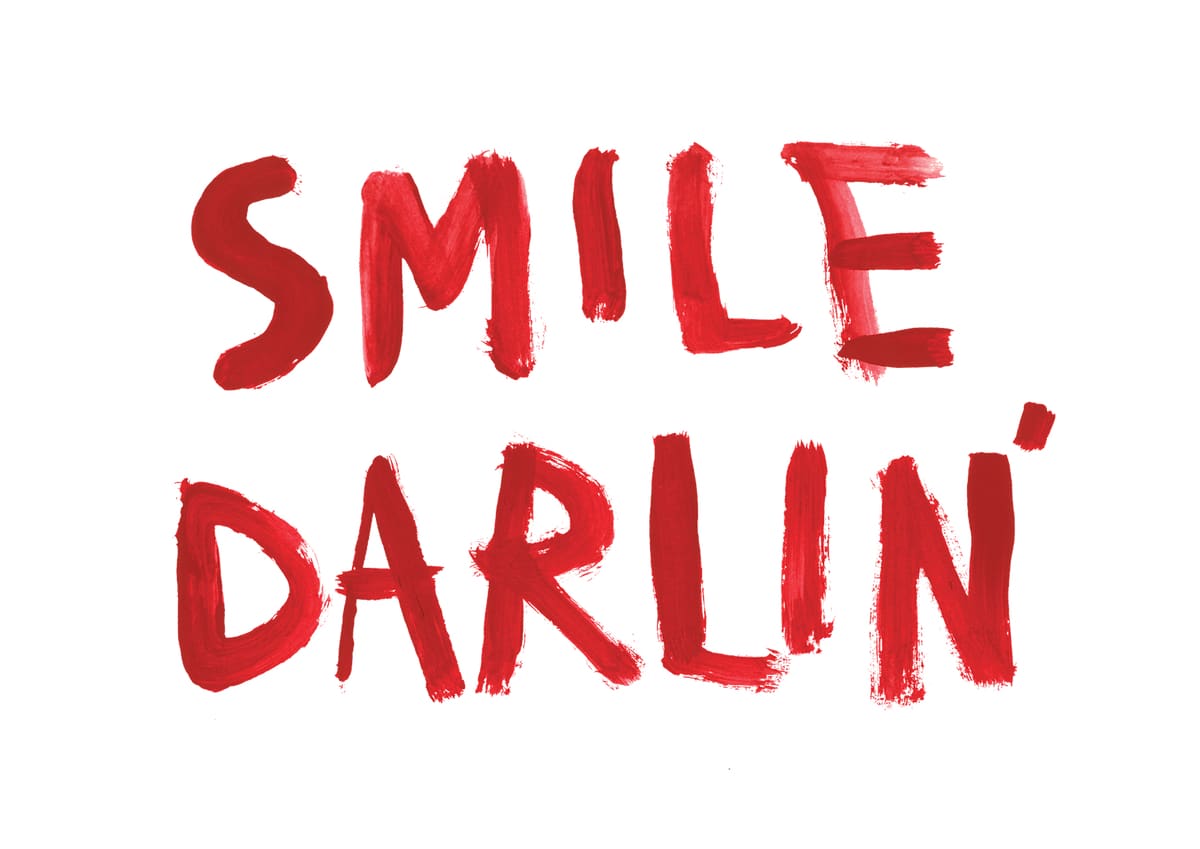

“You always hear “be safe on your way home” to a woman but you never hear “don’t rape anyone on your way home” being said to a man. We suffer the burden.”

“Why aren’t we teaching men not to rape instead of women how not to be raped?”

“It’s fucked up, that we just kind of got used to it.”

‘This isn’t about individual perpetrators. That’s a naive way to understanding what is a much deeper and more systematic social problem. The perpetrators aren’t these monsters who crawl out of the swamp and come into town and do their nasty business and then retreat into the darkness. […] Perpetrators are much more normal and everyday than that. So, the question is, what are we doing here in our society and in the world? What are the roles of various institutions in helping to produce abusive men?’ (Jackson Katz, 2012)

Potential perpetrators, these men, could be anyone, anywhere, at any time.

“People are like “oh, well it’s not all men” and no its not. But there are a lot of men who feel entitled to something from you, like groping you in a club, and of course it’s not everyone but it happens a lot.”

“My dad always says: “don’t trust any men”” “My boyfriend says that too.”

“Not all boys are bad.”

“But there are plenty that are.”

—

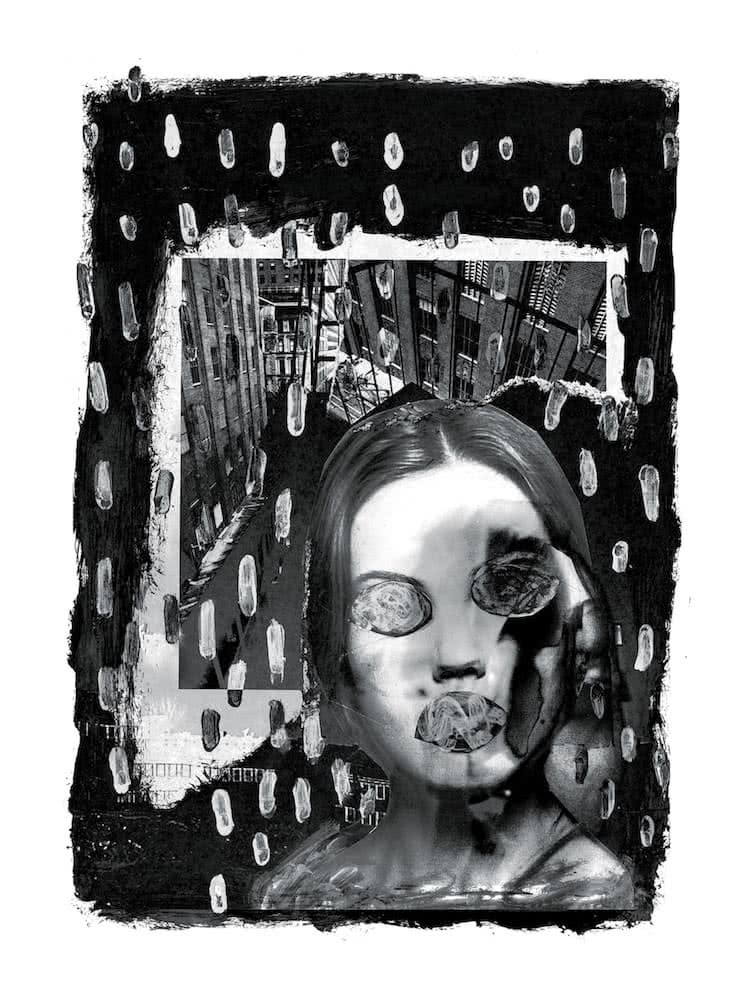

This is an extract from the visual essay ‘Walking the Long Way Home’ by Lily Jones. Lily is a mixed-media image-maker and writer whose practice based research concerns itself with gender politics and feminist issues.

All red dialogue is based upon content from a series of discussion groups on ‘Everyday Violations and Fears of Violence’, which took place at the Royal College of Art, White City, in December 2017.

The full essay with bibliography is available at furtherfeminisms.com.