April 11th, 2019

April 11th, 2019

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

The object has been liberated through a three-letter abbreviation preceded by a dot.

.obj

In the midst of a rapidly shifting digital landscape in the 1980s, the .obj file format was born, giving form to the 3D object in virtual space. A mass of coded data and coordinates; the .obj plotted the vertexes, vertices, (sur)faces, textures and the geometry of a three-dimensional object in a two-dimensional system. Initially developed for animation and 3D graphics, it is now one of many file formats that allow 3D objects, or even spatial models, to be rendered back and forth between reality and the digital realm. Almost four decades later, 3D technology enables us to produce everything from artificial organs, fully-functioning guns (one model of which is ironically named the ‘Liberator’) and architectural housing. It exposes controversial, even existential, ideas within society but it also presents new possibilities for how we imagine and record the landscape around us; fictional or real, fragmented Hyunsong Lee, V&A Cast Courts, 2018or whole. This is the starting point for .obj.

Hyunsong Lee, V&A Cast Courts, 2018or whole. This is the starting point for .obj.

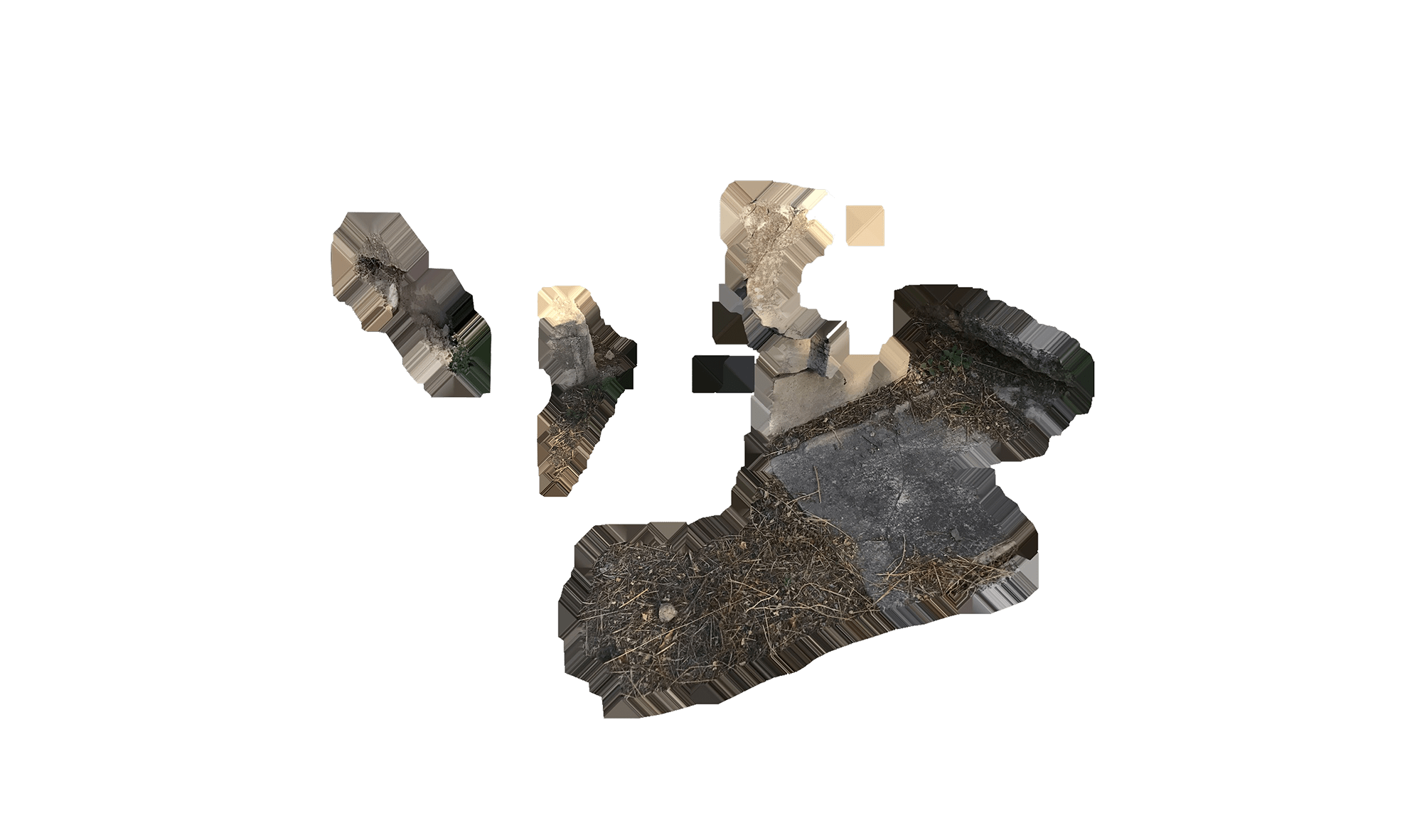

This collection of visual and textual essays both exemplify and grapple with the notion of the 3D artefact. Using a method known as Photogrammetry, objects are ‘captured’ James Gosnold, Acropolis of Athens, 2017 and mapped in multiple images, which are then meshed together to compose a virtual blueprint of the object. This idea of capturing not just an image, but a (fragmented) form that can be suspended in digital preservation, transformed and altered and then rendered back into reality

James Gosnold, Acropolis of Athens, 2017 and mapped in multiple images, which are then meshed together to compose a virtual blueprint of the object. This idea of capturing not just an image, but a (fragmented) form that can be suspended in digital preservation, transformed and altered and then rendered back into reality  An iterative process of reproduction gradually embeds the object with imprints of each stage of the process, such as light glares from glass vitrines and new topographical and textural surfaces.

An iterative process of reproduction gradually embeds the object with imprints of each stage of the process, such as light glares from glass vitrines and new topographical and textural surfaces.

Bex Liu, has been explored in relation to the ruins and artefacts of human existence.

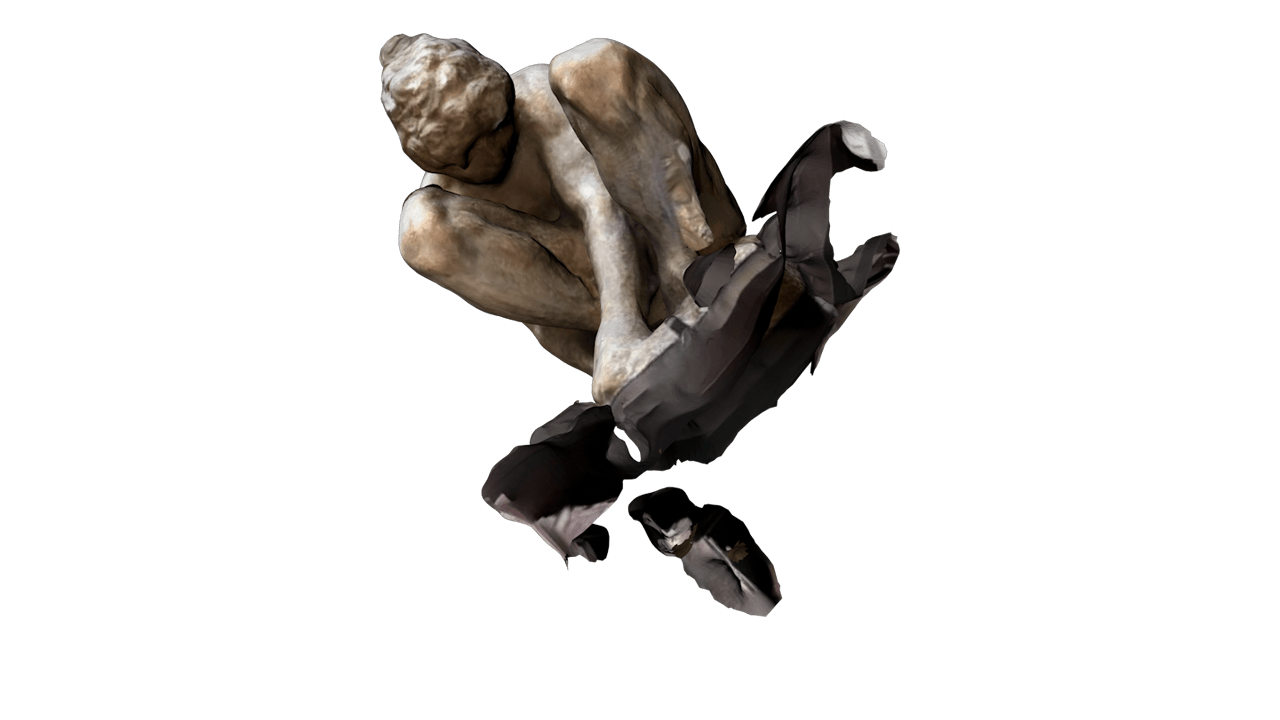

From the Athenian ruins in  In Athens I used 3D scanning as a way to capture and transport the monuments I witnessed as physical objects, letting the app take control of which parts / surfaces of the object are recorded and rendered into an object file.

In Athens I used 3D scanning as a way to capture and transport the monuments I witnessed as physical objects, letting the app take control of which parts / surfaces of the object are recorded and rendered into an object file.

James Gosnold Greece, to the famous Cast Courts at the This is an attempt to rethink the act and the symbolism of the copy, through creating another ‘cast’ of the Cast Courts collection.

This is an attempt to rethink the act and the symbolism of the copy, through creating another ‘cast’ of the Cast Courts collection.

Hyunsong LeeV&A, to the display cabinets filled with artefacts (Wunderkammer) Bex Liu, British Museum, 2018— the very nucleus of the British Museum; these captured objects have then been remixed into an alternate reality that is neither fiction nor fact. In its raw form, the .obj is made up of dissected and disassembled images, yet even in its fragmented and flattened state, it speaks to the sense of an absent whole: a contemporary digital ruin.

Bex Liu, British Museum, 2018— the very nucleus of the British Museum; these captured objects have then been remixed into an alternate reality that is neither fiction nor fact. In its raw form, the .obj is made up of dissected and disassembled images, yet even in its fragmented and flattened state, it speaks to the sense of an absent whole: a contemporary digital ruin.

The technology used to map and duplicate objects can be traced back to the Renaissance ‘polymath’, Leon Battista Alberti, whose algorithmic system allowed him to produce exact replicas of paintings, sculptures, and even buildings. The replica embodied enlightenment — it enabled spectacular sculptures, ornamental architecture and ancient relics The process of fragmentation of the object into jpeg pieces to build a 3D replica, is what inspired me for this visual essay.

The process of fragmentation of the object into jpeg pieces to build a 3D replica, is what inspired me for this visual essay.

James Gosnoldto be distributed and studied around the world. Creating copies became inextricably linked to forgery, but despite the negative connotations, plaster casts now occupy their own position within the canon of art history and reside in the permanent collections of museums. So in an age of endless possibilities, can 3D technology be used to shift conversations of preservation and cultural narratives?

The act of 3D scanning from museums, monuments, and heritage sites is somewhat of a grey area. As museums debate and move towards digitising their collections, this inevitably poses ethical questions of reproduction, value, distribution and ownership. Artists, Jan Nikolai Nelles and Nora Al-Badri, decided to challenge the ethical ramifications of the Nefertiti Bust, held by The Neues Museum in Berlin, by releasing their own 3D scan as a torrent file. When the V&A began to work with the project Scan The World, they found that 300 sculptures from the museum had already been scanned and uploaded by individuals. Much in the same way that the xerox copying machine altered visual production, the ability to scan and modify in 3D has already begun to create a seismic shift in the value and production of ‘artefacts’ This attempt to reencounter artefacts, removed from the bounding restrictions of museums and ‘cultural displays’, reimagines objects as repositories of memory and not of conservation and erasure.

This attempt to reencounter artefacts, removed from the bounding restrictions of museums and ‘cultural displays’, reimagines objects as repositories of memory and not of conservation and erasure.

Bex Liu and what the definition of an ‘artefact’ even is (see Forensic Architecture’s Bomb Cloud Atlas). The British Museum’s efforts to digitise their collection also resulted in the ability to reproduce scaled down Jesmonite figurines of famous sculptures within their collection to be sold in the gift shop for small fortunes.

The works featured in .obj embrace the lack of control over what the camera is able to collect and assemble and the flawed reproductions it generates. They propose an alternate model that can exist beyond the limitations of the ‘original’ or a singular narrative. Symbolic of the way that human memory works, the object is in The cast can be an alternative representation, adding historical and cultural layers.

The cast can be an alternative representation, adding historical and cultural layers.

Hyunsong Leeflux: the lens captures a fragmented and distorted image that can be edited and transformed, a constant work in progress or manifested into materiality. So is the .obj a form of abject liberation or merely another form of grotesque replication?

Excerpt taken from .obj, a publication written, designed and produced by Bex Liu, Hyunsong Lee and James Gosnold.