June 26th, 2021

June 26th, 2021

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

Walls are not barriers for hope and imagination. — Talha Ahsan, Otherstani

I had the endless day, months and months of endless days, and yet my return date bounded this sense of boundlessness, kept it from becoming threatening. — Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station

It feels strange to talk about transit after 18 months of standstill.

For the neo-nomads amongst us, lobby-room dwellers, coffee-shop inhabitants — the creatures of the transient who thrive in flux — the global lockdown created deep inertia. From the strange and transitory now, we are travelling back to when things stopped. When we entered standby mode, after go-go-going. When suitcase turned baggage within the confines of the home. When separation. When confinement. When George Orwell’s ‘Telescreen’ (1984) became a reality. When it felt like the end — terminus from Latin.

Terminal is not where; it’s when. It unpacks the broader questions when brought on. When everything is unmoving, uncertain and unprecedented, how do we change, create, grow? When in isolation energy is a limited resource, what can we afford to create? When art is deemed non-essential, how can sacrifices and compromises inform new values in the work we take into the post-Covid world — what is essential?

Although days in lockdown often felt like waiting at a bus-stop, we longed for public transport — a second home lost to the pandemic. It seemed that the best part of our thoughts had visited us on buses, on trains, on foot — in transit. So when inertia replaced hyper-mobility, at first, it felt like lost time. However, the relentless optimists in us chose to believe that no time was lost. Instead, we gained time: time for dialogue; time for crisis; time for grief; time for loneliness; time for re-imagining; time to start over; time to commit — time to think about what’s important.

We think of Tangier — the place William Burroughs called the Interzone in his letters to Allen Ginsberg shipped from Morocco to the US along with the draft chapters of ‘The Naked Lunch’ — where a plethora of artistic personas (Bowie, Kerouac, Bowles) met, traded their approaches, and exported these ideas to friends on other continents. In this terminal-like place, all dialogue and (sometimes illegal) activity was fruitful, however unproductive. Unlike Burroughs, no films were ever made from Paul Bowles’ stories, yet what’s left is a four-year long trail of long-distance correspondence with Tom Christie in New York. In a way, the last year has felt like a series of transmissions that didn’t “materialise” between the Interzone of Zoom and all twenty four time zones, leaving a sediment of draft recordings, process voice-notes and red herring transcripts — footpaths of storytelling — that which Donna Haraway classifies as essential to our Earthly survival.

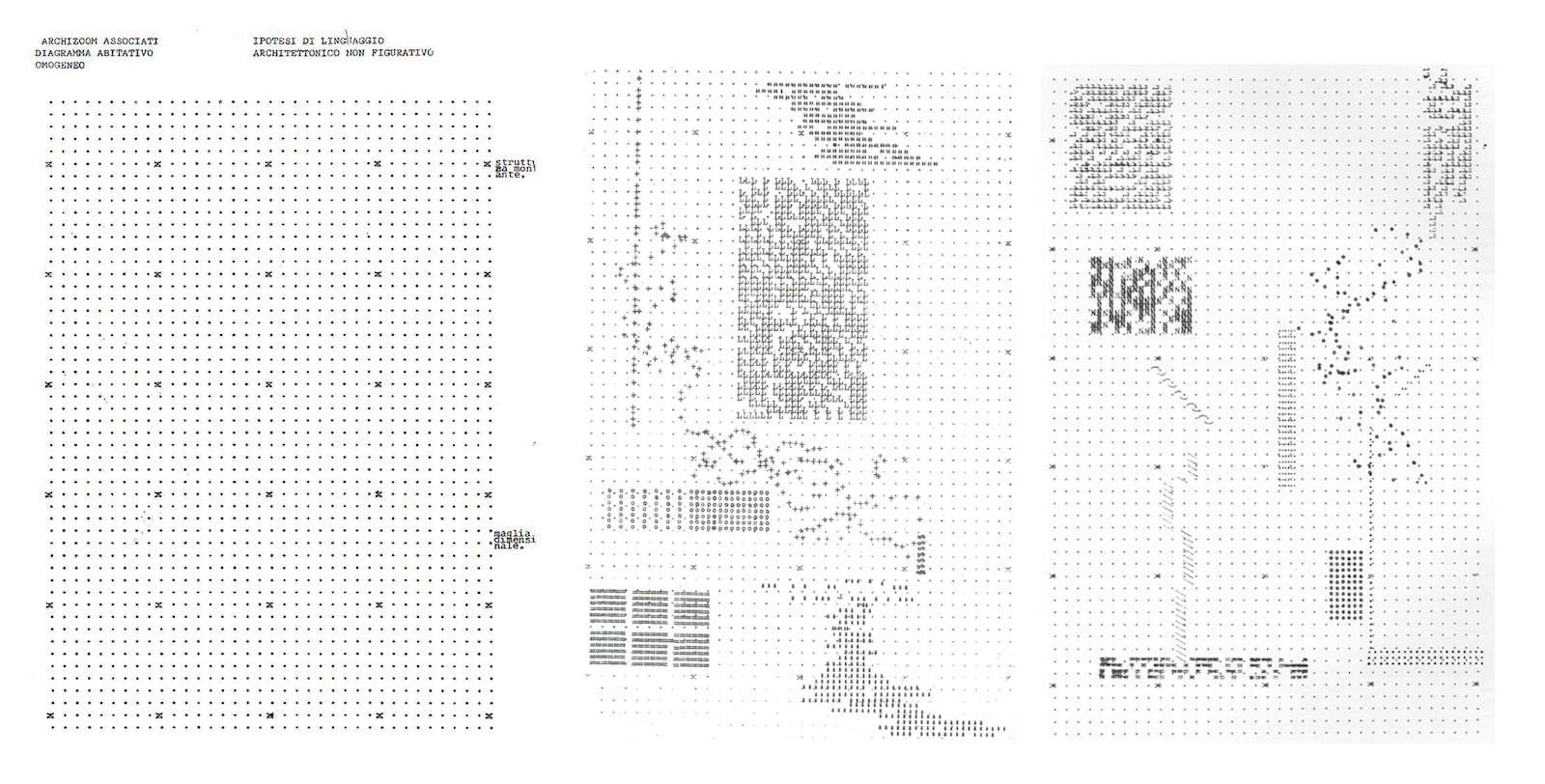

When Rachel Cusk’s narrator of Transit speaks of London as “one of the pre-eminent cities of the world” and how “adapting to it would make me feel strong”, she speaks to the flavour of strength acquired through surviving the brutality of the megapolis. For the contemporary practitioner who had already compressed their career inventory into only what you can carry between hireable workspaces and the patterned seats on the London Underground, this brutal adaptation had already been programmed into us; in lockdown, we just had to re-define it. We think of Archizoom’s Homogenous Living Diagrams precursive to No-Stop City — a grid-like space that emerged out of typesetting limitations (leading, tabs, indentation). Waiting to be programmed by end-users, the space describes a “loss of the distinction between interior and exterior”1. We think of coping-mechanisms and rituals that we invented to push back against the walls of our limits and to divide the invisible borders of work and home, whether it’s by walking a loop around the block or sweating out the bedroom office in the living room. In lockdown, we were all creative re-programmers of our spaces and of ourselves, re-adapting and re-imagining new domains within the confines of the home, which now housed temporalities and rhythms of the city.

Busy chasing dreams in the world outside, we often neglect the dream-scapes of our dwellings. As Hamja Ahsan advised in his “5 Tips for Artists & Curators in Lockdown” in Quaranzine!, we searched for inspiration in the overlooked corners of our personal spaces. We re-discovered, re-interpreted and re-grouped ephemera from old archives to keep our imaginations alive. We practiced patience. We looked closer. We left no pillow unturned. And then we saw domestic objects re-enchanted and sparkling in a new light. And then we saw scenic landscapes of memory re-animate. Then, we saw practices emerge out of an old family photograph. When physical spaces contracted, we saw spaces of care and consolidation expand. We saw resourcefulness and resilience amplify. We saw life-changing travel without leaving our desks. We saw how the contours of our beliefs and identities re-traced the shapes of our ancestors. In short, despite the sensation of having sat in a waiting room for nearly 18 months, we still saw this period as a prolific growth in critical thinking and making.

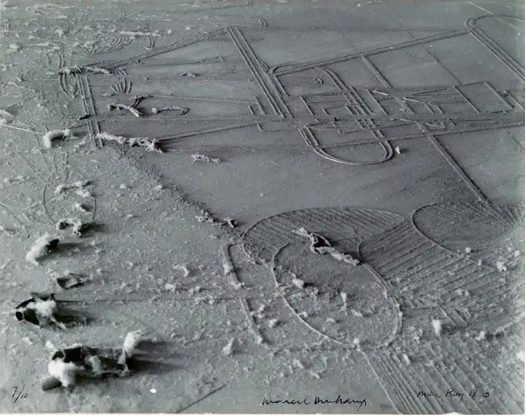

Whilst home-spaces bustle with overlaid temporalities and cram work-time, and play-time, and chill-time, and sex-time, public spaces inhabit a dystopian vacancy. It is usually us who wait for the city — for buses and trains to arrive, our rushed, over-scheduled journeys running late again — yet now it is the city who waits for us. We think of Man Ray’s Dust Breeding, the photograph Andre Breton called “a view from an aeroplane”. The original negative shows the edge of the dusty glass and a little of the studio beyond. Man Ray cropped it down, removing the spatial certainty, letting it become a separate world. This much discussed photograph that houses surrealist imaginations and projections of future cities, had taken on a new meaning in isolation. We see a city as a sleeping psychogeography, dusting over, whilst waiting for its inhabitants to start again, and perhaps redefine it. Terminal is when we finally blow the dust off, to reveal new possibilities that we couldn’t see before.

We transition from when to now. Now we think of the ‘unexpected’ — of random collisions with other passengers of life, of the strange yet familiar moments of insight and friendship that can only happen on a moving vessel, and of how their absence now feels even more important to living and imagining. Now a plexus of ideas and experimentations. Now trials and tribulations. Now power to intersections with the other, who will challenge our habits and customs. Now turning points and digressions.

Now we cross life-paths in a shared space. Terminal is a space and a time to celebrate the end of a transit that marks a beginning. Like closing an electric circuit, Terminal is only complete in the now, as a collective moment.

The Visual Communication 2021 MA graduates of the RCA, are pleased to welcome you on board of our concept-led physical show, TERMINAL. The show opens for private viewing on the 26 June (5.30am - 10pm) and is open to the public from the 27-30 June (10am-10pm), at Ugly Duck in Southwark, London.

TERMINAL brings together the work of over 50 students produced during (and in response to) isolation. This concept-led show unpacks the students’ experience of spending 18 months in a terminal-like space, and seeing it as an essential period in critical thinking and making. Visitors are invited to join this speculative space spread across nine exhibition Zones: Arrivals, Customs, Vestibule, Bus Stop, Declarations, Waiting Room (Library), Round Table, Control Room and Duty-Free.

TERMINAL features a programme of live performances, installations, moving image, sonic-work and expanded publishing, whilst also dialogic events such as workshops, seminars and poetry sessions. In addition, Visual Communication’s experimental Export Radio station will be transmitting soundbites from the event online.

Follow @terminal_rca on instagram.

References

Talha Ahsan, Otherstani

Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station, 2011

William S. Burroughs, Interzone, 1989

Kazys Varnelis, ““Programming After Program: Archizoom’s No-Stop City”

Tom Christie, “‘‘No Films Are Ever Made”: A Correspondence with Paul Bowles’’, Los Angeles Review of Books, August 20, 2018

Fabrizio Terranova, Donna Haraway: Story Telling For Earthly Survival, 2017

Rachel Cusk, Transit, 2016

Hamja Ahsan, “‘5 Tips for Artists & Curators in Lockdown”, Quaranzine!, edited by Mad Covid

André Breton, Littérature, 1922

Plates